In 2010, the Tea Party movement was born, sweeping a new breed of ultra-conservative Republicans to power in the House of Representatives. Whether you support or oppose the Tea Party, it's undeniable that these right-wing activists are the reason the GOP has become more extreme than in decades. On every issue -- from taxes, to background checks for gun sales, to birth control access -- the Tea Party has ensured that only the most ideologically pure candidates can win Republican primaries.

This observation is backed up by empirical research. Norm Ornstein and Thomas Mann, political scientists from the American Enterprise Institute, recently conducted a comprehensive study of party polarization in the US over the past several decades. [1] They found that American democracy is indeed becoming more partisan, but this polarization is all in one direction: the data shows the Tea Party has pushed Republicans to become radically more conservative on average, while the Democratic Party isn't much more liberal than in the past. [2]

In this post, we will model the long-term effect that this abrupt rightward shift among the Tea Party faction of GOP primary voters will have on the Republican Party over several election cycles. We'll illustrate how this sudden right turn drives moderate Republicans away from the party. Once these moderates leave the party the average ideological position of GOP primary voters will become even more extreme, which will push even more moderate voters away from the GOP. This death spiral will continue until the Republican Party shrinks down to an ultra-conservative kernel of hardliners.

To build our game theory model, we'll use a political science hypothesis that says elections are won by the candidate that reflects the political views of the average voter.

The Median Voter Theorem vs. The Mean Voter Theorem

For decades, political scientists generally agreed that the candidate most likely to win an election was the one whose views most closely aligned with the median voter. [3] To understand why, imagine if you could line up all the voters in a given election from most liberal to most conservative. The Median Voter Theorem assumes people vote for the candidate closest to them on this ideological spectrum. [4] So, the theory goes, the candidate that aligns his or her policy platform with the voter in the exact middle of the electorate will have the best chance of winning, because this position will necessarily be as close as possible to the views of the largest number of voters. [5]

The Median Voter Theorem is attractive to political scientists because if it's true, then relatively moderate candidates should win, keeping our political system stable over the long term. If elections are decided by the median voter, then extremists should have little influence over which candidates win, since no matter how extreme one side becomes, as long as the middle voter doesn't change their views the same moderate candidate will be elected.

The problem with this theory is that the policy platforms of today's Republican officials do not reflect the views of the median Republican voter. Here's a few examples of polls that back that up. The majority of GOP voters opposed the Tea Party plan to shut down the government [6]. The majority of Republican voters want GOP lawmakers to compromise on tax increases as part of budget deal [7]. An overwhelming 81% majority of Republicans favor background checks for private gun sales [8]. On the environment, only 26% of Republican voters deny the existence of climate change, while a whopping 60% want the country to take steps to address climate change [9]. On all of these issues, elected Republicans are clearly ignoring the majority of their party and doing everything they can to pander to the extremists -- the exact opposite of the outcome predicted by the Median Voter Theorem. So it appears this model does little to explain our current political climate.

The problem with this theory is that the policy platforms of today's Republican officials do not reflect the views of the median Republican voter. Here's a few examples of polls that back that up. The majority of GOP voters opposed the Tea Party plan to shut down the government [6]. The majority of Republican voters want GOP lawmakers to compromise on tax increases as part of budget deal [7]. An overwhelming 81% majority of Republicans favor background checks for private gun sales [8]. On the environment, only 26% of Republican voters deny the existence of climate change, while a whopping 60% want the country to take steps to address climate change [9]. On all of these issues, elected Republicans are clearly ignoring the majority of their party and doing everything they can to pander to the extremists -- the exact opposite of the outcome predicted by the Median Voter Theorem. So it appears this model does little to explain our current political climate.

Recent research suggests that there are many circumstances in which elections are determined not by the median voter, but by the mean (average) of all voters' ideological preferences. Stanford Professor Morris Fiorina explains that if candidates ignore the party loyalists in order to pander to the median voters, these loyalists can always decide not to vote -- for example, remember when in 2012 many Tea Party voters threatened to stay home rather than cast their ballot for Mitt Romney? [10] Moreover, political scientist Norman Schofield points out that if there are multiple issues at stake (for example, both social issues and fiscal issues) then it doesn't really make sense to talk about a "median" voter. In this case, Schofield argues, candidates position themselves towards the ideological mean, rather than the median. [11] He also finds the mean to be determinative when activist groups in one wing of the party have significant influence. [12] This is definitely true of the Tea Party, which is more likely to donate money or volunteer for Republican primary campaigns. [13]

Because of all of these factors, every voter is influential in determining who gets elected: every voter can decide to vote or not, to publicly endorse the candidate or not, to donate money or not, to volunteer or not, etc. So candidates must take all of their perspectives into account. The result is that the winning candidate is the one who represents the mean (average) point on the ideological spectrum of all the voters in that election, as opposed to the one that only appeals to the median voter. This competing hypothesis, on which we will base our model, is called the Mean Voter Theorem. [14]

We are going to test what happens in the primary elections if one faction of a party suddenly becomes much more extreme than before, assuming the Mean Voter Theorem is correct. Hopefully our simplified model will give us some insights into what long-term effects the Tea Party revolution will have on the Republican primary process.

Rules of the Game

Imagine that the Republican Party and the Democratic Party are each holding primaries for some hypothetical US election (we are not going to worry about general elections, just the primaries.) We will create a super simplified model to figure out the results of these (generic) primary races. Then we will see what happens over several election cycles if one of the Republican Primary voters becomes radically more conservative. Here are the rules:

- A total of ten people will vote in the primaries (just to keep it simple.) These ten voters can be lined up from most liberal to most conservative. Each voter can be assigned an "ideological score" depending on where their views are located on the political spectrum. The higher the number the more conservative they are, and the lower the number the more liberal they are.

- In the first election cycle, the voters' ideological scores are distributed evenly across the political spectrum from 1 to 10. The five voters on the left half of the spectrum participate in the Democratic Primary, and the five voters on the right participate in the Republican Primary.

- The winning nominee from each primary will be the candidate with an ideological score equal to the mean (average) of all the voters in their party.

- Voters have the option to change parties before each election cycle. If a voter casts their ballot in one party's primary, but the other party's candidate turns out to be closer to their views than the candidate nominated by their own party, then in the next election cycle they'll switch parties.

First Election Cycle: The Primary Results Are In!

Here's what the primary elections for the first election cycle look like:

Here's what the primary elections for the first election cycle look like:

We've said that the winner of each primary will run on a platform that represents the mean ideological score of each party. In this case, the Democratic nominee will have a score of 3, and the Republican nominee will have a score of 8. It just so happens that in this example, the median for each party is the same as the mean, but as we shall see, that is not always necessarily the case.

Second Election Cycle: The Right Wing Becomes More Extreme

After the primaries there would be a general election, the two parties' nominees would duke it out to win over independent voters. But we're just focusing on the primaries, so skip ahead in time to the next election cycle (so for example, if the first election cycle was in 2008, then if this were an election for US House of Representatives, which happens every two years, then the second election cycle would be in 2010.)

In the second election cycle, both parties will once again hold a primary. But what would happen if Voter J (the Republican voter all the way to the right) suddenly became way more conservative than he was the last time he voted? Let's say he joined the Tea Party movement and his ideological score jumped from 10 to 21 (and everyone else's views stayed the same.)

Notice that the median Republican voter still has a score of 8, the same as before. But now that Voter J is far more conservative, the mean Republican ideological score has gone up to 10.2, so the Republican nominee will now adopt this more conservative platform. Since the Democratic voters haven't changed their views in this example, their nominee will still have a score of 3 as before.

Third Election Cycle: Moderate Republicans Begin Switching Parties

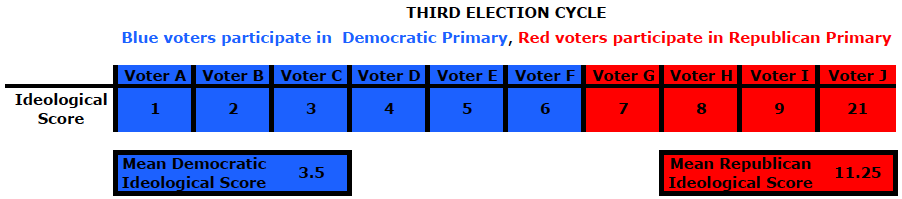

Consider Voter F, who has a score of 6. So far Voter F been voting Republican. But now the Democratic nominee, who has a score of 3, is closer to Voter F on the ideological spectrum than the Republican nominee, who has a score of 10.2 (i.e., 6 is closer to 3 than to 10.2.) So according to the rules we've established, Voter F will switch parties. Then in the next election, he or she will vote in the Democratic primary, since on average the Democrat's political positions are closer to Voter F's own views. The results of the primaries during the third election cycle are below:

Now that Voter F is participating in the Democratic Primary instead of the Republican Primary, Voter F's score of 6 is factored into the mean Democratic ideological score, pulling the Democrats closer to the center. The Democrats will elect a nominee with an ideological score of 3.5. The Republican Party, on the other hand, becomes more conservative on average, now that Voter F no longer casts his or her ballot in the GOP Primary. The Republican Party's mean score for this election is 11.25.

Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Election Cycles: The GOP Death Spiral

Next, consider Voter G, who has a score of 7. Even though Voter G always been a Republican, the new Democratic candidate (score = 3.5) is closer to them on the ideological spectrum than the Republican candidate (score = 11.25.) Therefore, in the next election cycle Voter G will switch parties and vote in the Democratic Primary. Here's what the primaries look like during fourth election cycle:

As you might of guessed, now that Voter G has started voting in the Democratic Primary, the Republican party becomes even more conservative on average relative to the Democrats. In the fourth election cycle, the mean Republican score is 12.67 and the mean Democratic score is 4.

This trend persists and the Republican Party continues to shrink. Voter H (score = 8) is now closer to the average Democrat than the average Republican, so Voter H switches parties in the fifth election cycle:

The mean Democratic score is now 4.5 versus a mean Republican score of 15. I bet you can guess what happens next: when the Republican Party moves further to the right, Voter I (score = 9) becomes a Democrat. Therefore, in the sixth election cycle the only Republican voter remaining is Voter J, the most right wing of them all:

Since Voter J is the only Republican left, the average Republican ideological score is simply Voter J's score, which is 21.

Conclusion

In our simple example, as the Republican Party becomes more conservative on average, moderate GOP voters leave the party, which makes the Republicans even more conservative on average, which in turn drives the next most moderate GOP voters to switch parties, until the only person willing to call themselves a Republican is Voter J, the single most conservative voter.

The surprising thing about this result is that only one voter (Voter J) has to change their ideological preferences to set in motion this downward spiral in which the party continues to shrink year after year, long after this voter initially changed their views. So as long as the primary elections are determined by the mean (average) ideological position of the primary voters, this ideological shift only has to happen once in order to make the collapse of the party inevitable.

Clearly the real world is more complicated than our simplified model. Keep in mind that the numbers I made up for the voters' ideological scores in our example were chosen only for the sake of concreteness. Additionally, it's possible that it could take a couple of election cycles before some moderate Republican voters decide to switch parties, even after the GOP no longer represents their values. In this case, the party migration we observed could take longer than in our illustration.

However, the basic dynamic demonstrated here helps explain why the Republican Party continues to become more and more extreme. The Tea Party revolution that started in 2010 dragged the GOP's center of gravity to the right, pushing center-right Republicans to leave the party, which has made the primary electorate even more conservative on average, further alienating moderates. Unless those who care about the future of the GOP find a way to keep the most radical elements of their base from hijacking the primary process, this death spiral will continue, and Republican Party will keep shrinking until they no longer have a large enough coalition to ever win a national election.

However, the basic dynamic demonstrated here helps explain why the Republican Party continues to become more and more extreme. The Tea Party revolution that started in 2010 dragged the GOP's center of gravity to the right, pushing center-right Republicans to leave the party, which has made the primary electorate even more conservative on average, further alienating moderates. Unless those who care about the future of the GOP find a way to keep the most radical elements of their base from hijacking the primary process, this death spiral will continue, and Republican Party will keep shrinking until they no longer have a large enough coalition to ever win a national election.